“Instead of loosening climate targets when Carbon Budgets are overachieved, the government should double down on mitigation efforts to lock in climate wins”

UK greenhouse gas emissions came in lower than target in 2018-2022 covering the government’s Third Carbon Budget period. This overachievement has raised the question of whether the Fourth Carbon Budget should be loosened in response to better than expected past performance on mitigating emissions?

The independent Climate Change Committee (CCC) is tasked with monitoring the government’s progress in climate mitigation under the 2008 Climate Change Act. It’s current focus is on progress towards two medium term targets: (1) to cut UK GHG emissions by at least 68% by 2030 in line with the UK’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to meet the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C; and (2) to cut the 5-year cumulative level of emissions to 965 MtCO2e by 2033-2037 in line with the government’s Sixth Carbon Budget. The Third, Fourth and Fifth Carbon Budgets are stepping stones to these medium term targets.

Past performance on mitigating emissions has been good…

The reduction in GHG emissions exceeded the government’s target by a little under 400 MtCO2e in both the Second and Third Carbon Budget. Article 13 of the 2008 Act allows the government the flexibility to carry over any surplus when emissions come in lower than target. An overachievement in one budget period can be carried over to increase the level of the 5 year carbon budget target in the subsequent period.

…but carrying over surpluses can create perverse incentives for governments

The problem with this flexibility is that it can lead to perverse incentives for policymakers. If the surplus of 391 MtCO2e in the Third Carbon Budget (2018-2022) is carried over in full, the Fourth Carbon Budget cap would increase from 1950 to 2341 MtCO2e (2023-2027). Since the outturn for emissions in the Third Carbon Budget was well below this level at 2153 MtCO2e, carrying over the surplus would effectively allow the level of emissions to rise in the next few years while technically still meeting the Fourth Carbon Budget. This point is well made in Piers Foster’s, Interim Chair of the Climate Change Committee, recent letter to the government.

Clearly it makes no sense to have emissions on a rising pathway to meet an overall objective of reducing emissions to Net Zero by 2050 in a way that minimises economic dislocation. Any increase would mean that emissions would need to be cut more sharply than otherwise at a later date to achieve Net Zero. It pushes the problem of mitigating emissions further into the future. It is already the case that mitigation is back-end loaded with more of the heavier cuts in emissions pushed out to the Fifth and Sixth Carbon Budget.

Even without carry over, following a budget overshoot there is less pressure on government to mitigate emissions

Moreover, even without carrying over surpluses, an overachievement of the carbon budget in one period automatically lessens the pressure on government to cut emissions in subsequent periods. This is because carbon budgets are set a long way in advance and are not revised for lower than expected outturns in emissions. The lower starting point for emissions in the Third Carbon Budget of 2153 MtCO2e means that emissions only need to be cut by 200 MtCO2e, or 40 MtCO2e per year, to achieve the Fourth Carbon Budget of 1950 MtCO2e (2023-2027). This is just one third of the planned cuts of 600 MtCO2e when the Fourth budget was set in June 2011 because of a lower starting point.

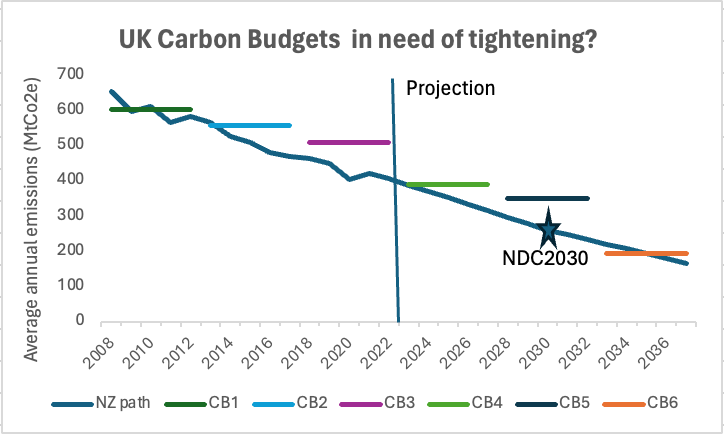

The bigger picture is that reductions of the order of 200 MtCO2e are not sufficient to put the government on course to meet its medium-term climate goals. The dark blue line in the chart below shows the smooth path for average annual emissions to meet the government’s NDC in 2030 and its Sixth Carbon Budget in 2033-37 against the average annual level of emissions implied by each Carbon Budget.

The chart shows that the cap on emissions set by the Fourth and Fifth Carbon Budget is far above where emissions need to be to achieve the UK’s NDC in 2030. Following a row back of climate commitments in September 2023 by the present government, the CCC finds that there is a “substantial policy gap to the UK’s 2030 goal” with around one fifth of required emissions reductions not covered by sufficient policy plans.

There are only six carbon budgets left to 2050; the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth have already been set and the Seventh will be set in 2025 covering the period 2038 to 2042. If the size of emission reductions continues at a pace of 200 MtCO2e in each 5 year budget period ahead, this would leave a rump of 1000 MtCO2e of unmitigated emissions by 2050 when the UK is supposed to have achieved Net Zero. This implies an average annual level of emissions of 200 MtCO2e, or that around half of the current level of annual emissions would remain unmitigated.

The implication is that short term Carbon Budgets are not serving their intended purpose of binding the government into ambitious policy actions to bring down emissions sharply enough to generate a smooth glide path to Net Zero by 2050. They send a confusing signal to individuals and businesses about the government’s climate commitments and the urgency of stepping up private investment in the low carbon transition.

Instead of loosening climate targets when Carbon Budgets are overachieved, the government needs to double down on mitigation efforts to lock in climate wins

There is a strong temptation for governments to continually push the problem of cutting greenhouse gas emissions further into the future. This allows them to simultaneously claim that climate targets are ambitious while avoiding the immediate costs of investing in the low-carbon infrastructure and the socio-economic changes to achieve these.

External factors, including the Covid-19 pandemic, have allowed emissions to fall faster than expected (recent analysis of energy data by Carbon Brief suggests that emissions continued to fall in 2023). Instead of loosening targets, the government should be opportunistic and double-down on climate mitigation efforts to lock in climate ‘wins’. This may mean that further legislation is needed to tighten up on Carbon Budgets that have already been set.

It follows the spirit of a precautionary approach to climate mitigation, as set out in Article 3 of the UNFCCC which establishes that: “parties should take precautionary measures to anticipate, prevent, or minimize the cause of climate change and mitigate its adverse effects.” Such an approach advocates early and ambitious interventions to respond to the highly threatening risk of irreversible climate change in the face of rising uncertainties. It creates space for unexpected external events that risk blowing climate mitigation off course.

Leave a comment